An anomaly in the behavior of neutrinos, nearly massless particles that rarely interact with other matter, has intrigued physicists for decades. In a paper published Dec. 3 in the Journal Nature, scientists on the MicroBooNE experiment have ruled out a long-standing hypothesis – the existence of a sterile neutrino – with 95% certainty.

New Mexico State University’s Department of Physics is part of the international MicroBooNE collaboration, which bridges 193 scientists from 40 institutions, national labs and universities across six countries. NMSU’s physics department has been involved in research at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, the facility that hosts MicroBooNE, since 1985. The MicroBooNE project itself started collecting data in 2015. The detector ran from 2015 to 2021, and scientists are still combing through and analyzing all the data.

MicroBooNE’s most recent discovery rules out the existence of a sterile neutrino.

“In our accepted model of the universe, there are three “flavors” of neutrinos: the electron-, the muon- and the tau-neutrino,” said Stephen Pate-Morales, NMSU physics professor emeritus and a collaborator on the MicroBooNE experiment. “Neutrinos have this interesting property where they can transform from one kind to another.”

However, there are gaps in this model. Previous experiments revealed an anomaly in the way neutrinos oscillate between these different “flavors.” This inconsistency gave rise to the idea of a fourth neutrino: the sterile neutrino. The MicroBooNE experiment was set up to investigate.

“What MicroBooNE was able to show is that these sterile neutrinos don’t exist,” Pate-Morales said. “If they existed, we would have been able to see evidence in the detector. And we did not.

“It happens a lot in science that something new is measured, and nobody understands it. So, a lot of hypotheses are made, and then you check them out, and some of them go away.”

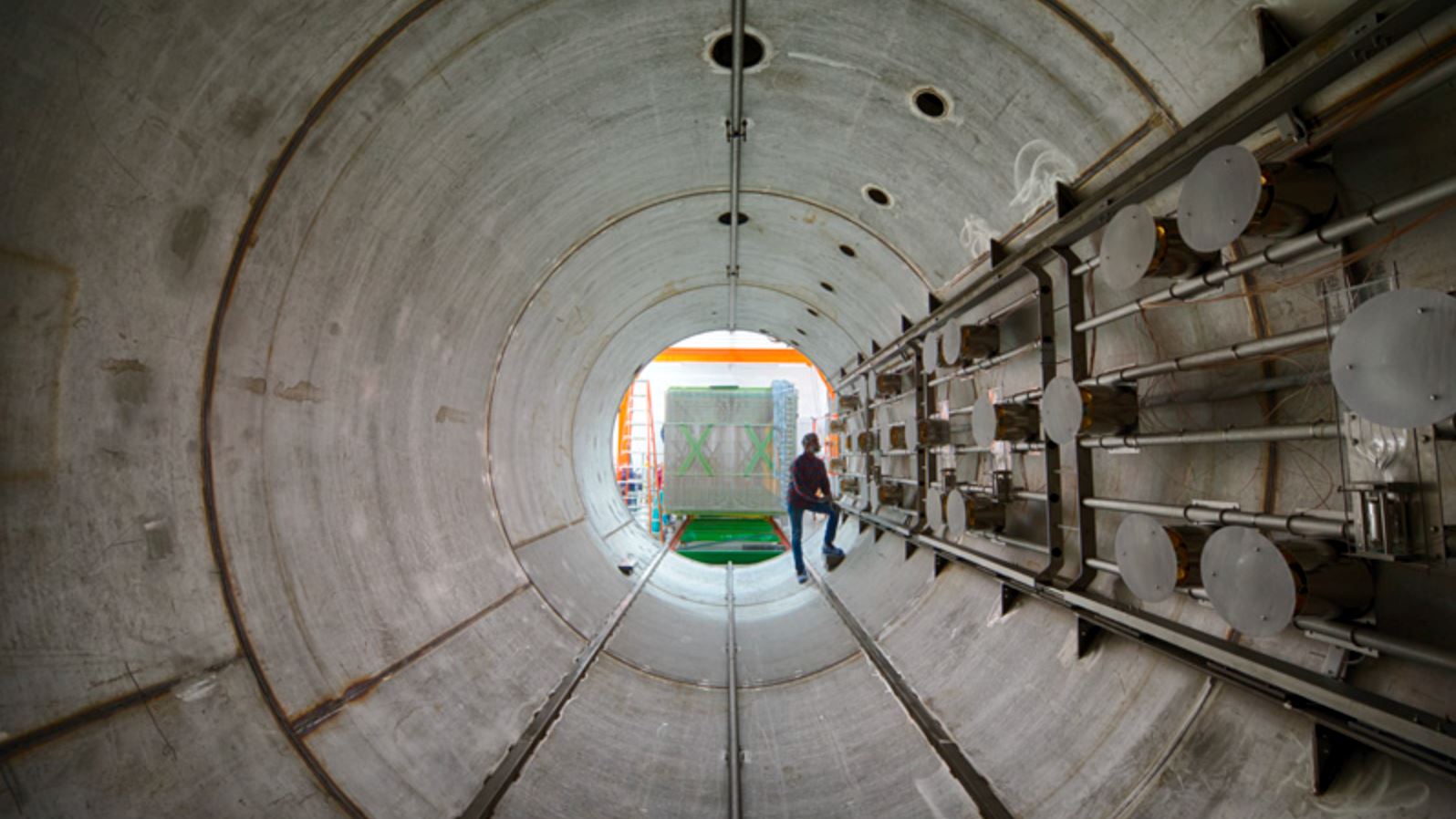

The MicroBooNE Experiment consists of two neutrino beams and one detector the size of a school bus. The giant detector, 40 feet long, 170 tons by volume and full of liquid argon, serves as the target for the neutrino beams. MicroBooNE is the world’s first two-beam neutrino experiment to collect detailed information on neutrino interactions.

Using a two-beam configuration allowed scientists to reduce the uncertainties within the experiment, almost entirely eliminating the region in which the sterile neutrino could have existed.

“MicroBooNE was built to check out this sterile neutrino idea. In order for it to be effective, it had to be a much better detector that the ones that came before it,” Pate-Morales said. “It’s able to record in great detail the identity and momenta of almost all the particles that are produced in any given interaction. This is a big leap forward.”

In ruling out the sterile neutrino idea, many questions remain unanswered.

“A pretty astonishing number of hypotheses associated with the sterile neutrino have basically been eliminated,” Pate-Morales said. “MicroBooNE was able to say that the sterile neutrino hypothesis didn’t work. It means these old anomalies still exist and we have to come up with another explanation.”

With sterile neutrinos now ruled out, MicroBooNE is moving on to analyze its remaining data, providing crucial information about neutrino interactions in liquid argon, and helping prepare for future experiments like the Short-Baseline Neutrino (SBN) Program and the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment (DUNE). The original anomaly in the neutrino data remains, and physicists are now exploring alternative explanations, such as more complex neutrino models or new physics like "dark matter."

-30-

CUTLINE: Workers install a component of MicroBooNE’s precision detector (called a time projection chamber) into the cylindrical container, or cryostat. (Fermilab photo by Reidar Hahn)

CUTLINE: Stephen Pate-Morales, New Mexico State University physics professor emeritus and collaborator on the MicroBooNE experiment. (KRWG photo by Emily Guerra)

CUTLINE: The international MicroBooNE experiment uses a 170-ton detector placed in Fermilab’s neutrino beam. The experiment studies neutrino interactions and has found no hint of a theorized fourth neutrino called the sterile neutrino. (Fermilab photo by Reidar Hahn)