Jul 17, 2025 - Learn about all aspects of the classification process across Para Alpine, Para Cross-Country and Para Snowboard in a dedicated series of six articles published ahead of the 2025-2026 season, culminating in the Paralympic Winter Games in Milano-Cortina.

Where Para sport is a celebration of athletes with all different impairments coming together, classification is the system that aims to ensure the utmost fairness across all competitions.

It is effectively a method of safeguarding, designed to level the playing field as much as possible. It means that success is a direct result of training, skill, and strategy, as opposed to the nature or severity of impairment.

Each athlete goes through an extensive process, from interviews with a Classification Panel to physical and, in some cases, technical assessments.

It will then be down to the classifiers – a person authorized and certified by FIS – to determine whether an athlete has an eligible impairment to compete and whether or not they meet the Minimum Impairment Criteria (MIC) to do so.

As much as these decisions are made regarding individual personnel, they are equally made with the wider sporting community in mind.

“The decision for an athlete is important, but if you make the wrong decision and place them in the wrong class, it could affect all other athletes,” explains FIS Head of Classification, Sandra Titulaer.

It works two ways – it’s not just [about] one person, but it’s [for] everyone.

– Sandra Titulaer, FIS Head of Classification

Para Classification: How does it work?

First things first: Does the athlete in question have an eligible impairment caused by an underlying health condition?

Eligible impairments are considered the following:

Impaired Muscle Power: Athletes have a health condition that reduces or eliminates their ability to voluntarily contract their muscles to generate force

Limb Deficiency: Athletes have total or partial absence of bones or joints because of trauma or congenital limb deficiency

Leg Length Difference: Athletes have a difference in the length of each leg

Hypertonia: Athletes have increased muscle tension and reduced ability of muscle to stretch, caused by damage to the central nervous system

Ataxia: Athletes have uncoordinated movements caused by damage to the central nervous system

Athetosis: Athletes have continual, slow involuntary movements

Impaired Passive Range of Movement: Athletes have a restriction or a lack of passive movement in one or more joints

Vision Impairment: Athletes have reduced or no vision caused by damage to the eye structure, optical nerves or optical pathways, or visual cortex of the brain.

If FIS concludes that they do, they are then invited to an evaluation session with a classification panel. This entails questions about medical diagnosis and training history; followed by a physical assessment and, if applicable, technical.

Within that, the panel may look at the following:

Muscle power

Muscle tone

Reflexes

Passive range of movement

Co-ordination

Motor control/movement control

Anthropometric measurements (this refers to the use of tools to collect relevant data needed to assess the health and growth status of the human body)

Visual acuity and/or visual fields

It is necessary for what comes next, in determining whether or not an athlete meets the MIC before being assigned a sport class. Sport classes indicate to what extent an athlete is able to perform the discipline in question. As a result, it helps to level the competition field, meaning that athletes with different levels of impairment can compete against each other in the same category.

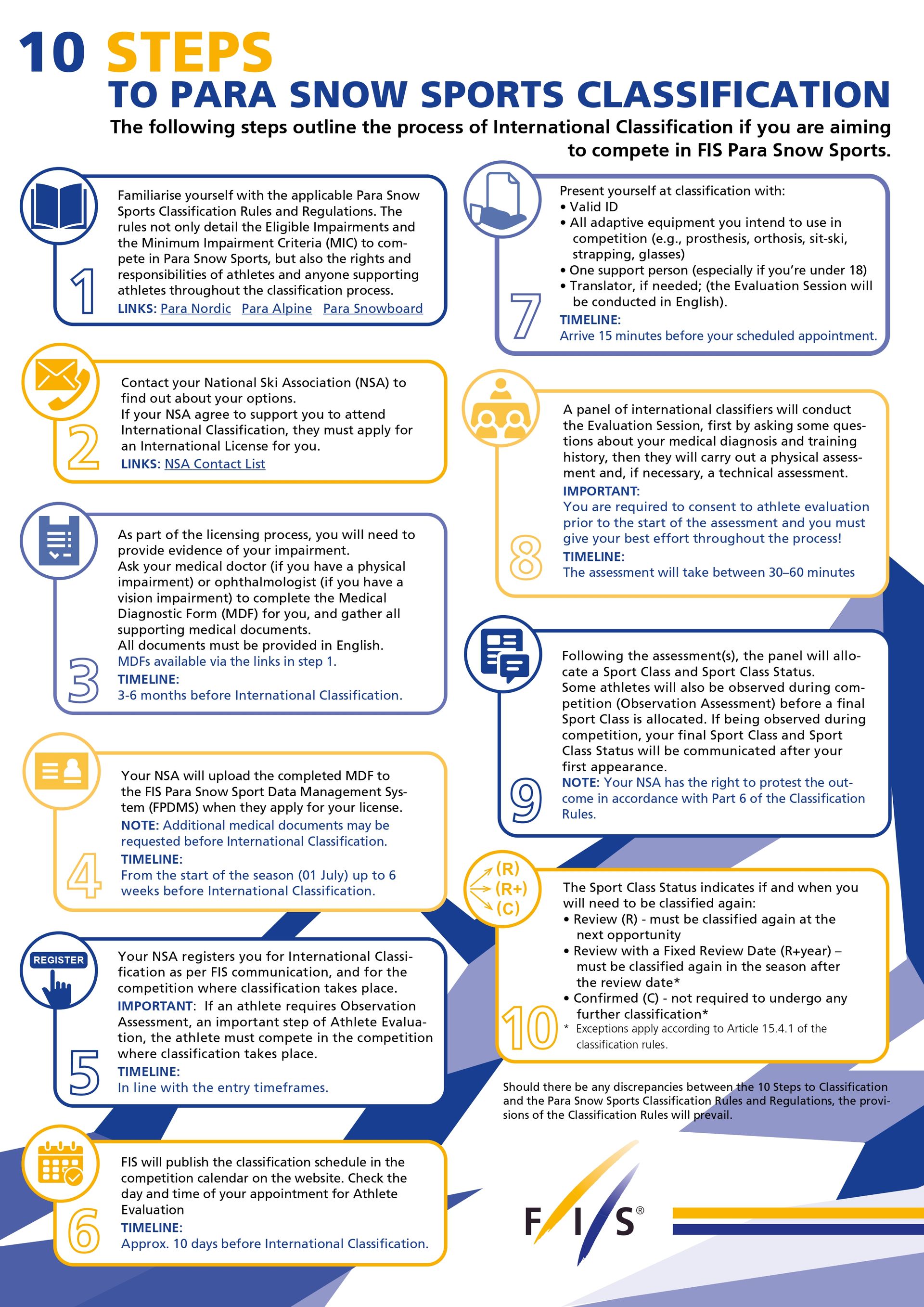

These are all crucial phases of the ’10 steps to classification’, which is a document that outlines the process for interested parties. From working with National Ski Associations (NSAs) right up until the decision, and possible appeals process, these steps detail the journey one must take in order to compete in Para sports.

While many of these steps are applicable to all FIS disciplines, being sorted in sport classes and achieving the MIC for each are sport specific.

Alpine Skiing, Snowboard, and Cross-Country have all evolved over the years and continue to do so as Para participation on the snow grows.

Below, FIS depicts the origins of each sport.

History of Para Alpine Skiing

Para Alpine Skiing has been on an upward trajectory since 1948, when the first official course was offered to participants. Its development can be dated back to the Second World War, with injured ex-servicemen seeking a return to the sport. The first official documented event occurred in the same year, where 17 athletes took part in Austria.

It wouldn’t be until the 1960s that the first classification systems for it were developed, built upon from those early revisions in Scandinavia. Like many sports, what began as a system to assess amputees only has evolved into a far more functional system that allows for impairments of all kinds, including sit skiers.

By 1976, the sport featured in the first-ever Paralympic Winter Games, held in Sweden, with two events contested: Slalom and Giant Slalom, contested by standing and visually impaired skiers. Sit-skiing was introduced eight years later as a demonstration discipline at Innsbruck 1984, before becoming a medal event at Nagano 1998.

As of now, there are five events under the Para Alpine umbrella: Downhill, Slalom, Giant Slalom, Super-G, Alpine Combined, and Parallel Team Events. Within these, athletes are categorized as one of the following: Sitting, Standing, and Visually Impaired skiers. Each category has their own sporting classes, which we will delve into in Part 3, that determines which factor will be applied to an athlete’s race time; this is applicable for both Alpine and Cross-Country.

History of Para Snowboard

The emphatic rise of Para Snowboard – formerly known as Adaptive Snowboard – can be chalked down to a group of riders who, in 2005, began their mission to have it included at the Paralympic Winter Games. Nine years later, it debuted at Sochi 2014 with two medal events in lower-limb impairment classifications.

Its evolution continued in the following year, debuting at the World Championships in 2015, featuring Slalom and Snowboard-Cross events. With the growth of the sport over the last decade, it now boasts five events that are practiced worldwide: Snowboard-Cross, Snowboard-Cross Team, Banked Slalom, Dual Banked Slalom, and Giant Slalom.

Since 2022, FIS took on the responsibility of acting as the federation for Para Snowboard, following the transfer of governance of Para Snow Sports from the International Paralympic Committee (IPC).

Para Snowboard features only one competition category: Standing. Within this category, athletes compete in one of three sport classes based on the assessment of their impairment. These are: SB-LL1, SB-LL2, and SB-UL.

LL – Lower Limb, meaning that athletes have an impairment in one or both legs

UL – Upper Limb, meaning that athletes have an impairment in one or both arms

LL1 and LL2 indicate the severity of the impairments in one or both legs, with the former comprising of a more significant impairment.

History of Para Cross-Country

Much like its Alpine counterpart, Para Cross-Country was one of the sports to debut at the inaugural Winter Paralympic Games in Örnsköldsvik, Sweden. It is a discipline that has enjoyed its fair share of evolution over the years, with skiers sticking to classic technique on the snow before the introduction of skating at Innsbruck 1984.

With this came the division of events, paving the way for two types of races: classical and free technique. The latter was officially used in a medal race for the first time in 1992. Sitting events were introduced at the Lillehammer Games in 1994, prompting yet further expansion of the discipline and its relevant classification practices.

There are three categories within this sport, all of which have varying sport classes, which are: Standing, Sitting, and Vision Impaired. Where equipment varies for the former two, the latter compete with a sighted guide who skis slightly ahead to deliver instructions to their accompanying athlete while on the snow.

As classification evolves, so does FIS’ commitment to the cause. Through until 2028, the organization is investing in long-term research to help improve accuracy and fairness.

You can read all about that in Para Snow Sports classification: Part One.

The third article in this series will delve deeper into Sport Classes, with a focus on different equipment types, and Minimum Impairment Criteria (MIC) across all relevant disciplines.